From data to decision in a coffee shop with two baristas

• Data → Mean → Standard deviation → Standard error → A/B comparison → z-score → Hypothesis testing → Decision

🟦 1. The Data — Customers Waiting for Coffee

Imagine you own a small coffee shop.

You have two baristas:

- 👩🍳 Anna

- 👨🍳 Ben

Every morning, customers queue up, and you start timing:

- How long each customer waits from order to drink in hand.

At this point, the data look messy:

- One customer: 18 seconds

- Another: 42 seconds

- A big order: 65 seconds

- A simple espresso: 14 seconds

You’re not doing statistics yet.

You’re just observing the world.

💬 Intuition:

Raw data is just reality recorded. It’s noisy and ugly – and that’s fine.

🟩 2. The Mean — “Typical” Wait Time

You’d like to compress all this into something like:

“How long does a customer typically wait with Anna?”

“How long with Ben?”

That’s where the mean comes in.

Suppose after timing many customers, you get:

- Anna’s average wait time: 28 seconds

- Ben’s average wait time: 31 seconds

The mean is the balancing point of all the data.

If you imagine every wait time as a weight on a number line, the mean is where the plank balances.

💡 Why the mean?

Because it’s the best single guess of “central tendency” when you care about squared error (which we’ll get to soon).

🟧 3. Standard Deviation — How Wild is the Experience?

Two baristas could have the same average, but very different consistency.

- Some days are smooth.

- Some are chaotic.

To capture this, we use standard deviation (SD).

- If Anna’s SD is 6 seconds, her wait times are tightly clustered.

- If Ben’s SD is 12 seconds, his times are more spread out.

💬 Intuition:

SD answers: “How much, on average, do individual wait times wiggle around the mean?”

🧮 Side Note: Variance and Squared Error

Variance is the average squared deviation from the mean.

Why squared?

- It ignores sign (Prevents negatives from canceling positives).

- Makes large deviations matter more

- It gives nice math: the mean is the point that minimizes the sum of squared errors.

💡 What does “the mean is the point that minimizes the sum of squared errors” actually mean?

👉 If you pick any number to represent your data, the mean is the number that gives you the smallest total squared difference from all data points.

This is an optimization statement.

Let’s break it down using developer mental models.

Imagine you have a list of numbers:

25, 30, 28, 29And you want one single value to represent them.

Let’s call that value M.

But how do you choose M?

🔧 Step 1 — Think of M as a “central” value

You want M to be close to all the values.

So you measure how far M is from each one:

distance = each value - MBut distances can be negative (e.g., 25 - 28 = -3), so we square them to make them always positive.

So we compute:

(25 - M)²

(30 - M)²

(28 - M)²

(29 - M)²And then add them up.

This gives us a score:

- Bigger score → M is a bad choice

- Smaller score → M is a good choice

🧠 Step 2 — Try different values for M

Try M = 10 → far from all numbers → huge score Try M = 100 → even worse Try M = 27 → getting closer Try M = 28 → even better Try M = 29 → also good, but slightly worse Try M = 40 → bad again

It turns out that the one single value that gives the smallest score is always the mean.

🎨 Developer-Friendly Metaphor

Think of each data point as pulling on a point M with a string.

If M is too far left → right-side numbers pull harder

If M is too far right → left-side numbers pull harder

Squaring the distances makes longer pulls much stronger

The mean is the exact point where all the pulls balance.

It’s the optimal compromise.

OK, I hope that clears it up, now…

Standard deviation is just: bringing the spread back to the original units (seconds).

🟨 4. A Crucial Shift: From Data → Estimates

Up to now, we’ve described the data itself. Now we change perspective.

Imagine repeating the same experiment:

- Today you sample 20 customers

- Tomorrow you sample another 20

- Next week, another 20

- Each time, you’ll get a slightly different mean.

So the real question becomes:

If we repeated this measurement many times, how much would our calculated mean wobble?

That difference between averages is what Standard Error measures.

Imagine throwing darts at a board.

- Standard deviation tells you how scattered the hits are.

- Standard error tells you how much your estimate of the bullseye would change if you kept playing multiple games

Intuition:

- A larger sample gives more information, so our best guess of the true mean becomes more precise.

- That’s why the uncertainty shrinks with √N.

Rule of Thumb:

- We have less uncertainty as we take more samples

- Doubling your sample cuts uncertainty by about 1/√2.

🟨 5. Standard Error — How Uncertain is Our Mean?

So far we’ve described the data (mean & standard deviation) and then how certain we are about the mean (SE). This next step uses that uncertainty to compare two means rigorously.

This is where people often get lost — so let’s slow down.

What Standard Error Is:

Standard deviation describes spread in your data.

Standard error describes spread in your estimates — that is, how much your calculated mean would vary across repeated studies.

If standard deviation is about individual variation, standard error is about estimation uncertainty.

We now know:

- The mean wait time (28s vs 31s)

- The SD (how much individual customers vary)

But here’s the deeper question:

“How uncertain am I about that average?”

If you only timed 5 customers, you’re not very sure.

If you timed 500 customers, you’re more confident.

This is what standard error (SE) measures:

Where:

- SD = standard deviation of individual wait times

- N = number of customers sampled

💬 Intuition:

SE is the uncertainty of your mean.

More data → √N grows → SE shrinks → your estimate sharpens.

Sampling Distributions

Our objective:

Standard error tells us not just what the average is, but how confident we can be about that average — which is essential for deciding whether a difference (like between Anna and Ben) is real or just noise.

🟥 6. Comparing Anna vs Ben — A/B Logic

Now we move from describing one barista to comparing two.

We define:

Interpretation:

- If → Anna is faster (smaller wait time).

- If → Ben is faster

But δ is based on sample data — so it’s noisy too.

Every measured mean has uncertainty, so the difference does too:

We need its standard error:

This comes from the rule:

If two estimates are independent,

variance of the difference = sum of their variances.

Since SE² = variance of the estimate, their squared SEs add.

💬 Intuition:

tells us how noisy this comparison is. If SE_δ is tiny, even a small δ might be meaningful.

If SE_δ is huge, you might be seeing random fluke.

🟪 7. Z-Score — Measuring Difference in Units of Noise

Now we compress everything (the entire comparison) into a single number:

This is the z-score.

It answers:

“How many standard errors away from zero is this observed difference?”

- → no meaningful difference

- → Anna is 2 SEs faster

- → Ben is 3 SEs faster

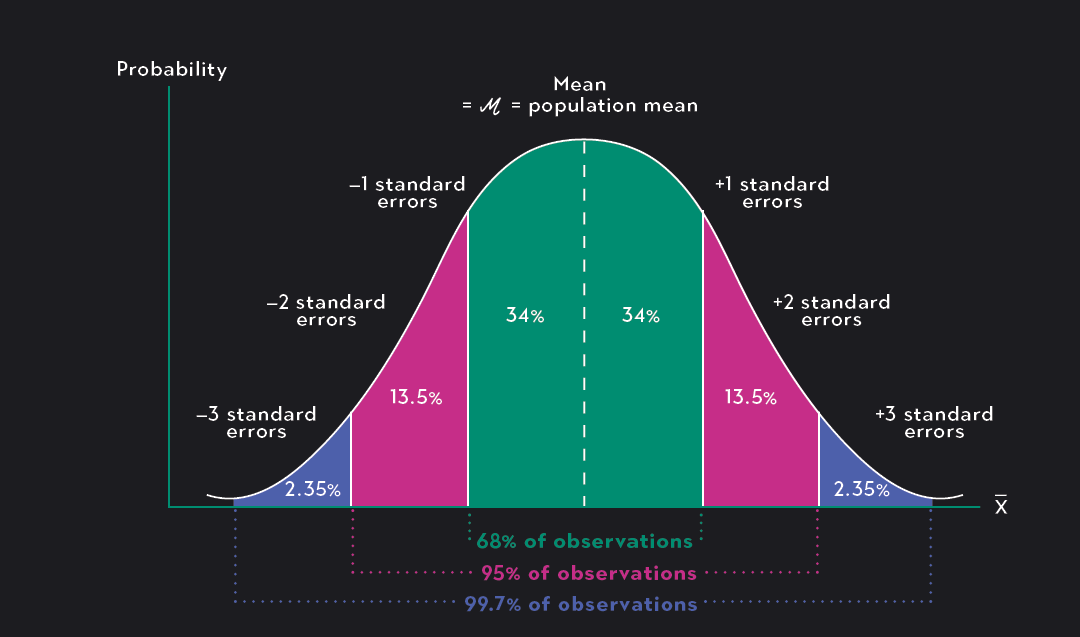

🧮 Sidebar: Why does z follow a bell curve?

Because δ is built from averages of many independent observations.

By the Central Limit Theorem (CLT),

those averages are approximately normally distributed,

no matter what the original data looked like (within reasonable conditions).

Dividing by SE standardizes it so:

under the assumption “true δ = 0”.

🟫 8. Hypothesis Testing — Turning Evidence Into Decisions

We now have:

- A difference, δ

- Its noise level, (uncertainty)

- A standardized score, z (standardized evidence)

Hypothesis testing wraps this into a decision rule.

🧩 The game:

-

Null hypothesis (H₀):

Anna and Ben have the same true mean wait time -

Alternative (H₁):

Anna and Ben differ or even directionally: Anna is faster -

Compute:

-

Ask: Under , with , how likely is a value as extreme as ours? how probable is a z as extreme as the one we observed?

This probability is called the p-value — it tells you how surprising your observed result would be if the null hypothesis were true.

-

Decision:

- If the p-value is small (say, < 5% or 0.05), act as if the difference is real, and route more customers to the faster barista.

- If not, you don’t have enough evidence yet.

⚠️ Important:

You never get certainty.

You get a bet with a known error rate (e.g. at most 5% chance of being wrong in this specific way). You get a controlled risk of being wrong.

🧭 9. The Whole Journey

Here’s the full progression from noisy data to decision:

💻 Example Code Snippets

import numpy as np

# Example wait times in seconds

anna = np.array([25, 30, 28, 29, 27, 26, 31, 24], dtype=float)

ben = np.array([32, 35, 30, 29, 40, 33, 31, 34], dtype=float)

def describe(x):

mean = x.mean()

sd = x.std(ddof=1)

se = sd / np.sqrt(len(x))

return mean, sd, se

anna_mean, anna_sd, anna_se = describe(anna)

ben_mean, ben_sd, ben_se = describe(ben)

delta = anna_mean - ben_mean

se_delta = np.sqrt(anna_se**2 + ben_se**2)

z = delta / se_delta

print("Anna:", anna_mean, anna_sd, anna_se)

print("Ben :", ben_mean, ben_sd, ben_se)

print("delta:", delta)

print("SE_delta:", se_delta)

print("z-score:", z)

🎯 10. Conclusion

We’ve traveled from raw data to decision-making through a logical chain:

- Observe — collect messy, real-world data

- Summarize — compute means to find “typical” values

- Quantify spread — use standard deviation to measure consistency

- Estimate uncertainty — use standard error to understand how confident we are in our estimates

- Compare — calculate the difference between groups and its uncertainty

- Standardize — convert to a z-score for universal interpretation

- Decide — use hypothesis testing to make principled decisions with known error rates

The beauty of this framework is that it’s general-purpose. Whether you’re comparing baristas, A/B testing website designs, or evaluating treatment effects in medicine, the same logical progression applies.

Key insight: Statistics doesn’t give you certainty — it gives you a principled way to make decisions under uncertainty, with known and controlled error rates.

📚 What We Didn’t Cover

This guide focused on building intuition for the core concepts. Here are important topics for further study:

- Confidence intervals — instead of just testing “is there a difference?”, estimate the range of plausible values for the true difference

- t-tests vs z-tests — when sample sizes are small (< 30), the t-distribution accounts for additional uncertainty in estimating SD

- Effect size — statistical significance doesn’t tell you if a difference is practically meaningful (a 0.1 second difference might be “significant” but irrelevant)

- Multiple comparisons — testing many hypotheses inflates your false positive rate; corrections like Bonferroni or FDR control help

- Power analysis — how to determine sample size before collecting data to ensure you can detect meaningful effects

- Non-parametric tests — alternatives when your data doesn’t meet normality assumptions